René Redzepi arrived in Asiago over 2000 years ago. He was probably rather short, had a beard, and came from Denmark: just like the chef from Noma. He hid with his partners in crime on the Altopiano – after he was defeated in a battle with Roman consul Gaio Mario, in 101 BC –, he settled down bringing his cultural and social, as well as gastronomic equipment.

The meeting-confrontation with the north is in fact the fil rouge in the entire history of the Sette Comuni. Sometimes there’s exchange or assimilation, as when, around and especially after the 1000 AD the plateau was once again invaded, peacefully, by southern Germany; these people emigrated in search of land to farm. The overlapping of Barbaric and German people established a local language, Cimbrian, of German origins (historians believe Cimbrians in the Sette Comuni derive from Gaio Mario’s Goth Cimbri, or from the Bavarians of 1000 AD: there’s no agreement on the issue); once widely spoken, the language now survives in Roana on the Asiago Plateau, in Giazza in Lessinia Veronese and Luserna in the province of Trento.

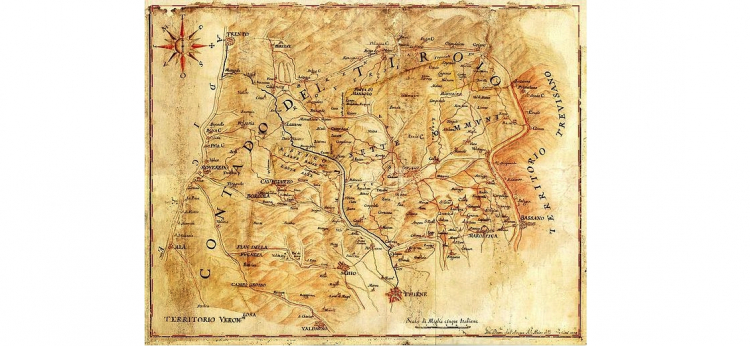

The Altopiano dei Sette comuni in a map of the territory of Vicenza by Giandomenico Dall'Acqua, 17th century. Vicenza, Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana

On other occasions the relationship between Asiago and the North was of counter-position: the

Spettabile Reggenza dei Sette Comuni (

Hòoge Vüüronge dar Siban Komàüne! in Cimbrian) was autonomous for centuries but also an ally of the Serenissima Repubblica di Venezia: it guaranteed a stronghold on the north-eastern border and the supply of wood, in exchange for military training, food and other privileges. Asiago was also the bloody battlefield between Italy and the Central Empires during the First World War, «the entire Altopiano was almost razed to the ground. Some “

case rosse” [red houses] – thus called because of their painted walls – became an emblem of rebirth. They were built as a place where wayfarers could rest. There were 7-8, now there are only 2 left. The local authorities want to give new value to them». These are the words of

Alessandro Dal Degan. Since December 2014 he occupies one of the two houses, the one in Kaberlaba, just off Asiago, with his

Tana Gourmet [the restaurant was born in the town centre, in 2008].

Please don’t think the historic background was superfluous, and I hope it wasn’t boring. Indeed it would be impossible to speak of Dal Degan's cuisine in its essence, without understanding the background livening it: «I use fermentations, musk, lichen, herbs, resin, wood. Basically a culinary culture typical of Northern Europe. I’m not following fashion or a passion for New Nordic Cuisine. On the contrary, I’m recuperating a local tradition». He was born in Torino in 1981, but his mother and grandmother are from Asiago, and both cooks.

The

Tana Gourmet red house, at 1,100 m above sea level, dominates the surrounding scenery but is also enclosed in a crown of mountains that forms the border of the Altopiano, as if it was a bucket, making it a sort of microcosm that for centuries has been impenetrable by the outside world, with an orographic vocation for isolation. So it’s almost this geographic position that suggests the natural vocation of

La Tana Gourmet as a place in which this small culinary world can find its perfect synthesis.

Dal Degan accomplishes this in two ways: in the nearby Osteria, born a couple of years ago, where he serves traditional dishes, «really traditional: from Tagliolini in broth with chicken liver to Tripe and Asiago cheese, a typical shepherds dish»; then, at La Tana Gourmet, with his creations «that have nothing to do with tradition». Or, rather: which draw inspiration, techniques, products from these culinary roots; and then these elements are innovated in the chef’s interpretation.

He says: «Here at

Tana we only prepare what we have in mind, without any discount», without trying to please. It’s true: his cooking is strict, sometimes even difficult, but always filtered with a sense of taste that allows it to be fully harmonious. The dishes are very elegant, they present the surrounding world in a contemporary and fascinating way: they recreate an almost forgotten culinary history, based mostly on the use and preservation of vegetables long forgotten in cookbooks. This is why «we collaborate with two microbiology research centres: we must understand what’s happening in our experiments, where we’re heading when we change food, either through cooking or fermentation».

This scientific-experimental method is applied to cooking: «We start with raw materials, process them then study the results», the recipe is the latest step in this process. «After the snow melts, when it returns in the autumn nature offers us around 200 spontaneous vegetal varieties here. Perhaps only for a few days, like wild asparagus». This heritage must be enhanced «but without being obsessed with 0 km. We use a lot of what surrounds us, but our world, even the culinary one, doesn’t end here», and goes beyond these mountains.

Dal Degan and Enrico Maglio

loves sour, bitter, umami flavours («I like oriental culture»). They often appear in his dishes, but always in perfect balance: we move from one taste peak to the other, but always under control; he adds neither sugar nor salt, because he wisely makes use of the aromas that are in fact the essence of each ingredient. The staff is young and energetic, «the eldest is my partner

Enrico Maglio [

dominus of dining room and cellar. Then there’s the other partner

Stefano Fracaro, who’s in charge of the administration] and he’s 37. I’m 36, the other eldest in the brigade is 24». Yet there’s strong awareness and structure in everything they do. Mountains make you grow up earlier.

Dal Degan is very proud of his work and likes a challenge, like when he presents his new dish:

Pasta, tomato and herbs, a super Italian classic but turned upside down, with the pasta made with dough to which he added roasted tomato, and then seasoned with black garlic, more tomato and herbs (marjoram, tagetes, olive herb…). The result is remarkable, different, unpredictable. In fact throughout our meal there are moments of genius: in the raw veal heart that becomes a dessert, or in the dessert where he recuperates the tradition of mugolio, a syrup made with mature pine cones from mugo pines, left in the sun, in a glass jar, so as to melt their external sugar coat.

The Altopiano is a world of aromas, Dal Degan is its contemporary demiurge. As you’ll see in the photo gallery by Tanio Liotta.

Translated into English by Slawka G. Scarso