We can open a hundred dictionaries, but in the end the meaning of empathy doesn’t change, as recalled by Treccani: it’s «The ability of putting yourself in someone else’s place or, more precisely, of understanding immediately someone elses’ psychic processes». And it was to empathy that Molino Quaglia dedicated the 14th edition of PizzaUp at the school in Vighizzolo d’Este, Padua.

A difficult topic, because for the participants, all pizzaioli, it required going far beyond their usual reality. Journalist Cristina Viggè finely summed this up by quoting the famous pipe/non pipe painted by René Magritte. Just like that was not an authentic, chargeable and smokable pipe, since it was a drawing, so it came natural to state that Ceci n’est pas une pizza. Except that in the case of the event promoted by the Quaglias, the pizzas are real, like the ones that the participants imagine and prepare, cook and serve basically every day.

Launching the three-day-event in Vighizzolo was Massimo Donà, who came as philosopher, not jazz musician – he plays the trumpet. He launched the first lesson of the first day with words that made everyone understand that they were set to leave on a journey high above the usual, on new routes, very different from the past: «All of you should write in your restaurant that that place is not a pizzeria and what people are eating is not a pizza, it is not justa pizza. People will look at you surprised, but it is that “not” that encloses the mystery of life».

A professor at San Raffaele’s Università Vita e Salute in Milan, his words were not easily forgotten. It would be impossible when you start by saying that «eating a pizza is not an innocent act», which is what almost everyone believes instead, not understanding that you must be ready when you approach the most Italian dish in Italy. Empathy is the keyword. There are three very different levels of being empathic: «The first is doing without something of yourself and paying attention to the needs of the other. The risk in the end is that of no longer being yourself. Of giving up on your specific diversity.

Then there is the level on which we find a common element. It’s the land in between. You preserve a certain margin, but it’s also a schizophrenic position because, when you’re no longer yourself, but you’re not someone else either, you lose your identity».

The right empathy is in the third level, the most authentic because it enriches your identity and it’s what happens when a person understands «that what is different in others is not only different, but it is what makes us become even more ourselves. So when we eat, we bring in ourselves the outside world, which becomes an intimate part of ourselves, and in the long run we become more authentic». Hence pizza in fact is not pizza, it must be considered in the sense of never getting to know everything, of making clients understand that every margherita sets a moment apart, and it will never be the same upon the next visit because the world of the pizzaiolo will be richer by that time. The very contrary of industrial, and standardised products.

Simone Padoan, maestro pizzaiolo, patron at Tigli in San Bonifacio (Verona)

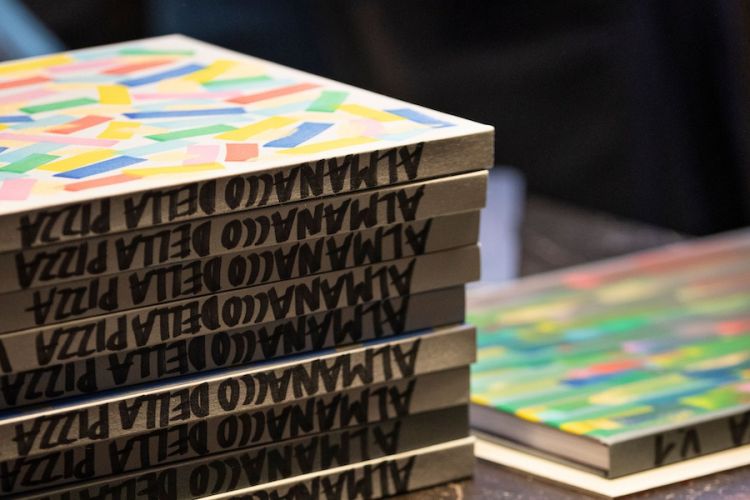

And the third day, big finale with the presentation of the first volume of the Almanacco della Pizza a collection of the “original souls who are writing the history of pizza”. In the words of Chiara Quaglia and Piero Gabrieli in the introduction: «We are attracted and we attract critics, passionate and farsighted people, who challenge those who stand looking without exposing themselves, and live the change to give the past a contemporary value. In this Almanacco there are 13 pizzaioli of this kind, starting from the person who caused the first sparkle». That is to say Simone Padoan, greeted by an endless applause. And after the Venetian pizzaiolo, Gennaro Battiloro, Renato Bosco, Marco Farabegoli, Daniele Donatelli, Massimo Giovannini, Massimiliano Prete, Lello Ravagnan, Giuseppe Rizzo, Giovanni Santarpia, Corrado Scaglione, Friedrich Schmuck and Massimo Travaglini. Cristina Viggè wrote their stories, with a postface by Corrado Assenza and photos by Thorsten Stobbe.

Translated into English by Slawka G. Scarso