There was no sign of chefs and cooking on television. Corrado was hosting Il pranzo è servito on Canale 5 at 1 pm but it was a quiz show. A few years earlier Stefano Bonilli hosted Di tasca nostra, a show for consumers, but there was no trace of it. The Ristoranti d’Italia dell’Espresso guide, inspired by French Gault&Millau, was meant for professionals: it was directed by a famous “fake beard” (the term used for secret agents), Federico Umberto D’Amato, whose identity was unknown to most, as he was head of the Private Affairs Office at the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Newspapers had a page dedicated to agriculture: I used to write about wine, from time to time, in the one edited by La Stampa. The only specialised magazine with a decent national distribution was historic Cucina Italiana, with many recipes and little news. When on the 16th December 1986 the eight-page insert was published with il manifesto, the response was sceptical. How long would it last?

Paris, 1989: it’s the 21st December, at Opéra-Comique the International Movement for the Defense of and the Right to Pleasure is officially born. The manifesto is signed by delegates from Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Denmark, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, United States, Sweden, Switzerland, Hungary, Venezuela

It’s title was

Gambero Rosso, like the tavern invented by

Carlo Collodi in

The Adventures of Pinocchio (this is where the Fox and the Cat would dine before continuing their journey to the Field of Miracles), and was directed by Rai reporter

Bonilli. A young “revolutionary” who had read Sociology in Trento and then took on a political career in Bra, in the secluded

Provincia Bianca of Cuneo was collaborating:

Carlo Petrini, known as

Carlin. These pages were a mix of irony, commitment, erudite articles and critiques by debuting “scarehost”

Edoardo Raspelli. The success was unexpected. On Tuesdays, the insert contained in the “Communist newspaper” directed by

Valentino Parlato made sales reach 80 thousand copies, twice the sales of a normal day.

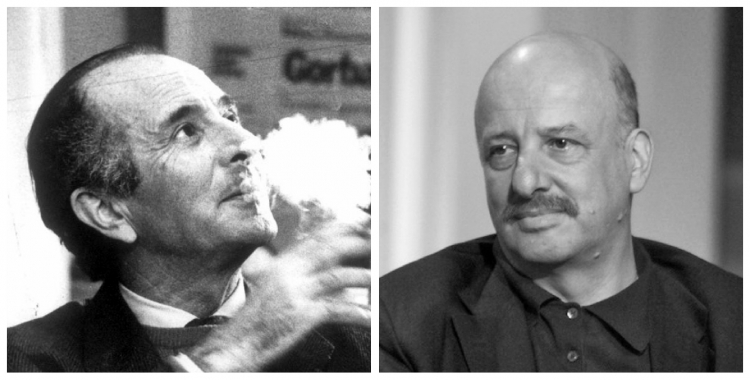

Carlin Petrini and Dario Fo

I remember I didn’t miss a copy, and collected them scrupulously. In 1975 I was a student and an activist at university. I met

Carlin in the headquarters of his

Radio Bra Onde Rosse, in the days when even

Dario Fo came running to defend it when it was requisitioned.

Petrini speaking from the microphone in 1989 in Paris; next to him Folco Portinari

Valentino Parlato and Stefano Bonilli

An Arcigola membership card from 1987

The turning point came as a surprise 30 years ago, when they published the “per vivere meglio” [in order to live better] appeal. The cover featured a word that changed food language for good: “

Slow-food”, written like this, with a dash. It came as a reaction to the opening of a fast food in the centre of Rome, in Piazza di Spagna.

Petrini had founded

Arcigola one year before. At the time, they’d meet in a tavern called

Unione in Treiso, in the Langhe region: what with tajarin and some good Barolo,

Folco Portinari, who was then a director at Rai, a critic and a refined poet, got the right idea.

Portinari wrote the text,

Petrini collected the signatures and on the 3rd November 1987 the manifesto was published in

Gambero Rosso with a snail designed by

Gianni Sassi. The signatures of

Portinari, Petrini, Bonilli, Parlato, were followed by those of famous intellectuals and artists such as

Dario Fo,

Francesco Guccini,

Gina Lagorio,

Enrico Menduni,

Antonio Porta,

Ermete Realacci,

Sergio Staino and more.

It was a rather snob and “situationist” break against the “comrades” who had become used to sloppy, anonymous food.

Petrini at a parade in Torino for Terra Madre in 2016

Why retrace this story and recall it today, thirty years later? Because without that experience of

Slow Food which was ground-breaking for gastronomy, and made it popular – says the president of

Slow Food Italia from 2006 to 2014,

Roberto Burdese – today there would be no

MasterChef,

Salone del Gusto,

Eataly, the

Identità Golose congress and all this media attention to food.

Petrini with Gigi Padovani

and I have been friends for 40 years and I suggested we go through this history with a book: I did so with a first volume in 2005. And now, with

Slow Food. Storia di un’utopia possibile, we were working together once again to retrace the journey of these past 12 years. A new book was born in which we show how an association born for well-fed people became a political movement that also fights for those who have an empty belly.

2006: a thousand chefs at Salone del Gusto-Terra Madre

This happened thanks to two great intuitions

Carlin had:

Terra Madre, the extraordinary 2004 novelty which welcomes food communities fighting for biodiversity and environmental sustainability in 160 countries across the world, and

Università di Scienze Gastronomiche in Pollenzo which has scattered two thousand graduates around the world who now have high quality food as their belief.

So today the movement promoting “good, clean and fair” food has become a “common good”. Everyone has seized it, including entrepreneurs like

Guido Barilla, Giuseppe Lavazza, Oscar Farinetti, Alessandro Ceretto, who told me in the book how

Petrini and his ideas influenced them. Perhaps this is the new challenge for

Slow Food, take a new leap, as decided during the congress in Chengdu in China: gradually dissolving into

Terra Madre and becoming an increasingly “liquid” movement.

The publisher wrote in the book’s preface: «This is the official “biography” of the

Slow Food movement, the “story of a possible utopia” that started from a small town and conquered millions of people around the world», with an «editorial hand», the one of a journalist [the author of this piece] «that transcribed the words of

Petrini avoiding him the understandable embarrassment of writing about himself». A nice Italian story that now belongs to everyone. (Many interviews included in the book are also available as videos, on

www.claragigipadovani.it).

Translated into English by Slawka G. Scarso

Slow Food. Storia di un’utopia possibile

by Carlo Petrini and Gigi Padovani

Giunti-Slow Food Editore, 356 pages,

September 2017, 18 euros (15,30 euros if you buy it here)